The Fundamentals for Managing Anxiety

By: Brian O'Sullivan, M.S., LMFT

This article aims to give a concise blueprint for managing anxiety. The goal is to provide a comprehensive overview that will direct you to other articles that go into more depth on particular skills or aspects relevant to managing anxiety.

Disclaimer: The resources provided here are not a substitute for therapy. The information presented is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as therapy, psychological advice, or be used for diagnosis. Nothing on this website establishes a therapist-patient relationship. For personalized guidance, please consult your physician or mental health provider.

What is Anxiety?

Anxiety is our brain sending a false alarm and has two essential parts:

- Our brain perceives something as a threat that isn't a threat and sends us alarm signals.

- We believe the alarm signals to be accurate and act to protect ourselves from the perceived danger.

False alarms feel identical to real alarms, and we experience these cognitively (thoughts) and in our bodies (feelings):

Cognitive:

- "What if?" thoughts

- Worst-case scenario thoughts

Feelings:

- Racing heart

- Sweat

- Stomach pain

- Shaking

You can learn more about the different types of anxiety and anxiety disorders in this article.

Ruling Out Medical Conditions

Before getting too far with therapy or self-help strategies, going to a trusted medical professional is the first step. Certain medical conditions can cause or negatively influence existing anxiety. Having a solid medical baseline before working on your anxiety can save you a lot of time and money in the long run.

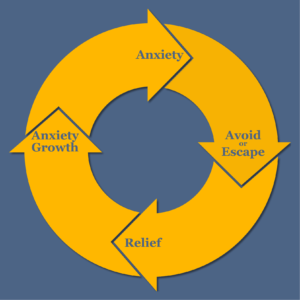

Understanding The Anxiety Cycle

The diagram below represents how anxiety is created and maintained. Having a solid understanding of it increases our awareness of the things we are doing that inadvertently maintain anxiety and helps guide us away from these unhelpful behaviors.

Anxiety begins with a trigger. The trigger can be external (e.g., a busy mall, seeing someone you don't get along with, or a confined space) or internal (e.g., noticing your heart flutter, a scary or worried thought about the future, or a persistent pain in your body).

The brain, through our senses, picks up this trigger and instantly perceives it as a threat. As a result, it sends us signals to alert us of the danger: racing heart, sweaty palms, shaky limbs, shortness of breath, stomach pain, etc.

This is the brain pulling the internal fire alarm. Other parts of our brain hear this alarm, perceive it as a sign of danger, and quickly send us urges to avoid and run away.

We get rewarded when we act on these instinctual urges and eliminate or escape the trigger. Our brain turns off the fire alarm and stops sending us uncomfortable physical sensations.

However, this short-term reward is at the expense of long-term anxiety maintenance and even anxiety growth.

As long as the trigger wasn't an actual danger (and most triggers aren't), we inadvertently traded short-term comfort for long-term discomfort.

Why does avoiding or escaping lead to long-term anxiety growth? Let's look a little deeper at the brain to answer this question.

Understanding The Brain's Threat Detection System (TDS)

The brain has an incredible threat detection system (I will refer to this as "TDS"). The TDS is always online, scanning for possible dangers, and it's the first to react to a perceived danger. Here are important characteristics to know about the TDS:

- It operates below our awareness

- It responds instantaneously when it senses danger

- It values safety over accuracy

- It's wired to overreact

An example of the TDS: Imagine coming home after a long day, you open the front door, and a loved one pulls a prank by jumping out from behind a door while screaming and popping a balloon in their hand. Your TDS takes complete control, and you instantly jump back and scream. All this happens before you're consciously aware of what's happening.

The TDS also considers how we react when it pulls the fire alarm. If we respond in a way consistent with danger (e.g., running away or avoiding), it takes note of this and believes it to be confirmation that the situation is dangerous. As a result, it will pull the fire alarm in the same situation (or similar situations).

Going back to the Anxiety Cycle, this is why anxiety is maintained long-term when we engage in avoidant or escaping behaviors. We inadvertently teach the TDS that there is a danger and to keep pulling the fire alarm. Anxiety is maintained and even grows.

Teaching the Threat Detection System (TDS) New Lessons

The good news is the TDS can learn new lessons. However, we can't teach it using logic and language. The TDS only learns through experience.

Also, the TDS can only learn when it believes there is a danger and has pulled the fire alarm. In other words, we can only teach it a new lesson when feeling anxious.

To illustrate how the TDS learns and how it does not imagine going to a Halloween carnival and walking up to the haunted house attraction. Before you step inside, a carnival worker pulls you aside and gives an hour-long presentation about how safe the attraction is. "It's been open 25 years, and there hasn't been one injury. Not even a stubbed toe."

No matter how convincing the presentation is, you will get triggered once inside. Why? Though the carnival worker has good intentions, he's wasting his time because the TDS doesn't understand language or logic.

The way to teach the TDS the haunted house is safe is by repeatedly going inside the haunted house.

This is the general formula for calibrating the brain to decrease the intensity of false alarms and increase their accuracy.